Part 5 – Fundamental Confusion: Management Vs. Leadership

Unfortunately, there are no universally accepted definitions for either leadership or management. Hundreds of definitions exist for both. However, leadership can be defined as a process of social influence that maximizes others’ efforts toward achieving a goal (Kruse, 2013) or a series of complex interactions between the leader and stakeholders in the organizational environment (Dalakoura, 2010). On the other hand, management is often defined as the coordination and administration of tasks to achieve a goal (Indeed, 2020).

These definitions do not suggest that one is necessarily better than the other. Such definitions merely demonstrate that a difference exists. Therefore, when considering roles, confusing the two may hinder desired outcomes due to confusion regarding expectations. While not an emphasis in this examination, an important note is that other roles, such as human resources, may also be confused with leadership and have similar issues that result from such confusion.

These confusions may set the stage for masked organizational toxicity and performance issues. This article merely highlights a couple of the more pressing cause-and-effect components that either contribute to or result from such confusion. However, similar to previous articles in this series, there is a circular issue impeding resolution in many cases. An examination of the components provides an opportunity for resolution.

Brief History of Management

While some scholars have argued that management traces back to Biblical times (Lloyd & Aho, 2020), most scholars agree that management as we currently understand it can find its true roots emerging in the late 1800s during the Industrial Revolution (Gunther-McGrath, 2014; Wood, 2018). The Industrial Revolution brought about advanced means of production and the need for a larger organizational structure and controls (Gunther-McGrath, 2014).

Enter Henri Fayol’s 14 General Principles of Management and Frederick Winslow Tayler’s Principles of Scientific Management between 1900 to 1910 (Brillinger, 2000; Wood, 2018). Since then, universities and researchers have dedicated numerous theories and academic degrees to the management discipline, and recent advancements such as project management, business process management, and drive theory ensure that management will remain a worthy counterpart to the leadership discipline for some time to come (Lloyd & Aho, 2020; Maryville University, n.d.).

Brief History of Leadership

As recently as 2013, some scholars considered leadership an emerging discipline (Riggio, 2013). However, the study of leadership actually goes back thousands of years. In his book, Leadership, Northouse suggests that leadership’s roots can be traced back to Aristotle (2016).

In truth, leadership goes back even further. Aristotle was a student of Plato, who wrote The Republic, which outlined three specific leadership types (Busse, 2014). Shriberg, Shriberg, and Kumari argue that, from a literature standpoint, leadership goes back even further, having been a central issue of exploration in the Iliad of Homer (2005).

Today, and unbeknownst to many, the study of leadership is now arguably one of the most popular in social science. Active research includes a wide range of examinations spanning organizational development to neuroscience. Accordingly, there are numerous leadership theories, academic leadership degrees at every level, and several peer-reviewed journals dedicated to the science of leadership and its development. This is an important point when considering the discussion in Part 4 of this series.

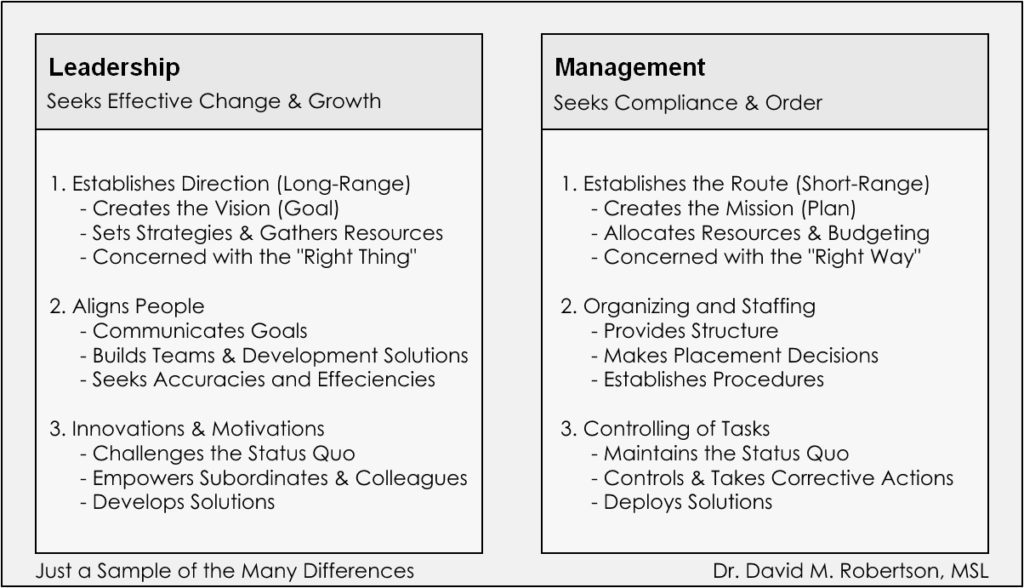

Both management and leadership are robust disciplines, and much more could be written on the history or current state of either management or leadership. This article is not meant to hash out every nuance. Instead, the preceding provides essential contexts for the following points and warnings. However, a brief listing of differences may help the discussion. While generalized and situational, the following image helps to demonstrate some of the many differences between the two.

A Warning – The Need for Role Clarity in Organizations

Words have meaning. As demonstrated, leadership and management define two different disciplines and roles. Informed scholars urge organizations to know the difference. For example, in an article in the Harvard Business Review titled, Management is (Still) Not Leadership, leadership expert, Dr. John Kotter, says that businesses and other organizations make the mistakes of confusing leadership with positions, using management and leadership interchangeably, and confusing leadership with characteristics (2013).

Other informed scholars emphasize the same and insist that leadership is its own discipline, as evidenced by its focus on vision, innovation, inspiration, and development (Busse, 2014). Shriberg, Shriberg, and Kumari point out that while management and leadership might share some characteristics, each discipline remains distinct and separate (2005). As such, a person can be a skilled manager or leader, or both, or neither (Shriberg et al., 2005).

Ambiguity and False Empowerment

For organizations seeking accuracies, efficiencies, and productivity, role clarity is critical. This is especially true if the organization or individual seeks a specific outcome where ambiguity is limited. In their discussion regarding group processes, Weinberg and Gould suggest that role clarity enhances a team’s effectiveness and adds that players will be more critical of the leader when they perceive ambiguity in their roles (2019). Specifically, blurred and uncertain role expectations can hurt the team and burden the worker. Therefore, leaders must help set and clearly define the roles if they seek to improve overall performance.

The previous point is essential when change is on the line. Dr. John Kotter said it best when he said, “Nothing undermines change more than behavior by important individuals that are inconsistent with the verbal communication. And yet this happens all the time, even in some well-regarded companies” (2012, p. 10). In the context of this article, organizations must be highly cautious about requesting leaders by title but demanding management by deed. Among other things, using these titles interchangeably may inadvertently cause inconsistency and role confusion or be seen as false or bogus empowerment by workers who understand the differences between management and leadership.

In her book, Ethics: The Heart of Leadership, Joanne Ciulla points out that when leaders and organizations offer empowerment but do not deliver, it is called bogus empowerment (2004). Ciulla argues that bogus empowerment results in a higher degree of cynicism and alienation (2004). The point becomes powerful when one considers some of the consequences of cynicism resulting from using such titles interchangeably. For example, one might expect cynicism from an employee sent to leadership development, only to discover that the organization expected compliance and the status quo upon return. Another example might be cynicism that results from hiring someone under a leadership banner only to discover that the position is entry-level or has limited leadership potential.

Employee Cynicism

Employee cynicism should be a consideration of paramount importance for organizational leaders. Cynicism is often the effect of a toxic organizational culture cause. Organizational culture issues such as negative attitudes, distrust of lying managers, the silencing or belittlement of issues, and overall distrust in the organization often result in cynicism, but organizations must also understand that cynicism is a direct contributor to change effort failures (Demirci, 2016).

It behooves organizational leaders to proactively identify and address the various factors that result in or contribute to cynicism. The specific warning here is that the cynic often cares little about the need or benefit of change and may harbor feelings of distrust towards those responsible for the change initiatives (Repovš et al., 2019). Accordingly, if the organization allows or encourages the contributing factors to go unchecked, lies and change hindrances or failures must be expected. Organizational and leadership development can help. However, there is a catch.

Development Confusions

The confusion and complexity regarding the differences between management and leadership often complicate the leadership and organizational development discussion (Simic, 2020). After all, it is exceptionally difficult to address a problem that has not been properly identified. Similarly, this confusion muddies the waters regarding leadership and leadership development options in the marketplace. Therefore, and to the potential detriment of either the organization or the worker, sometimes the need and the potential remedy are also confused and misaligned. This is true in either internal or external programs.

It is logical to assume that if the development program and the organization’s goal are not correctly aligned, the opportunity for failure increases. Therefore, organizations benefit by understanding the differences and aligning the organization and training programs accordingly. However, this is often easier said than done.

If the organization desires a better manager, but the development program is leadership specific, the program and the developed worker may not align well with the organization’s intended goal. Similar misalignments may occur when organizations desire leadership development but unknowingly contract or hire a novice practitioner who teaches management or pseudo-leadership principles. Hence, when it comes to the program’s outcome or evaluation, the organization or evaluator may assume failure despite the confusion that preceded the attempt.

When such failures occur, and the underlying confusion is not properly identified, future development opportunities are likely to be neglected or avoided, and organizational performance may continue to decline. Meanwhile, the various misalignments, confusions, and development failures will continue to contribute to role ambiguity, role confusion, and worker cynicism, which all contribute to and often describe organizational toxicity. As demonstrated, the issue is often circular. However, its resolution is likely rooted in understanding the difference and navigating accordingly.

Much more could be written on this topic, as there are many other issues that arise from such confusion. Organizations are encouraged to explore this topic further for clarification purposes and evaluate what part they may be playing in the problem. However, the warning is simple. It is wise for both individuals and organizations to understand the difference between management and leadership and to operate, hire, and train by definition. Doing so will allow organizations to be more strategic in their approach and realize better outcomes.

The overall takeaway of this article is that management is not leadership. The fallout of such confusion often contributes to ambiguous expectations, employee cynicism, and organizational culture toxicity, which will likely increase difficulty regarding the initiation or sustainment of change initiatives. In part six, the discussion turns to organizational culture specifically and what organizations must understand and do about related organizational issues.

_________________________

The Articles in this Series:

- Part 1: Organizational Development Needs

- Part 2: The Reality of Leadership Development

- Part 3: Leadership Development Evaluations and Limitations

- Part 4: The Right Trainer & The Novice Factor

- Part 5: Management vs. Leadership

- Part 6: Organizational Culture

_________________________

Use of this work is permitted with proper citation.

Acknowledgments & Actions

- Thank you for examining this research. Be sure to share if you find value in it, and be sure to check out the other parts of this series.

- This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

Brillinger, R. (2000). Management history’s broad sweep and putting people into project management. Canadian HR Reporter, 13(14), 8.

Busse, R. (2014). Comprehensive leadership review – literature, theories and research. Advances in Management, 7(5), 52–66. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ronald-Busse/publication/331564071_Advances_in_Management_-_Comprehensive_Leadership_Review_-_Literature_Theories_and_Research/links/5c80e83492851c69505c984b/Advances-in-Management-Comprehensive-Leadership-Review-Literature-Theories-and-Research.pdf

Ciulla, J. (2004). Ethics, the heart of leadership (2nd ed.). Praeger.

Dalakoura, A. (2010). Differentiating leader and leadership development: A collective framework for leadership development. Journal of Management Development, 29(5), 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011039204

Demirci, A. E. (2016). Change-specific cynicism as a determinant of employee resistance to change. Is, Güc: Endüstri Iliskileri Ve Insan Kaynaklari Dergisi, 18(4), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.4026/2148-9874.2016.0329.X

Gunther-McGrath, R. (2014, July). Management’s three eras: A brief history. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/07/managements-three-eras-a-brief-history

Indeed. (2020, December 2). What is management? Definitions and functions. Indeed. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/what-is-management

Kotter, J. (2012). Leading change. Harvard Business Review Press.

Kotter, J. (2013, January). Management is (still) not leadership. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/01/management-is-still-not-leadership/

Kruse, K. (2013, April 9). What Is Leadership? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinkruse/2013/04/09/what-is-leadership/?sh=79ea64b55b90

Lloyd, R., & Aho, W. (2020). The four functions of management. Digital Pressbooks. https://fhsu.pressbooks.pub/management/

Maryville University. (n.d.). A timeline of the history of business management. Maryville University. https://online.maryville.edu/online-masters-degrees/business-administration/history-business-management/

Northouse, P. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice (7th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Repovš, E., Drnovšek, M., & Kaše, R. (2019). Change ready, resistant, or both? Exploring the concepts of individual change readiness and resistance to organizational change. Economic and Business Review for Central and South – Eastern Europe, 21(2), 309–337. https://doi.org/10.15458/85451.82

Riggio, R. (2013). Advancing the discipline of leadership studies. Journal of Leadership Education, 12(3), 10–13. https://doi.org/10.12806/V12/I3/C2

Shriberg, A., Shriberg, D., & Kumari, R. (2005). Practicing Leadership: Principles and Applications (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Simic, I. (2020). Are managers and leaders one and the same? 2. Ekonomika, 66(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5937/ekonomika2003001S

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2019). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology (7th ed.). Human Kinetics.

Wood, S. (2018, March 22). Where it all began: The origin of Management Theory. Great Managers. https://www.greatmanagers.com.au/management-theory-origin/